Racial and Geographical Disparities in the Federal Death Penalty

Racial and Geographical Disparities in the Federal Death Penalty

Issues Highlighted by the Juan Garza Case

Findings of the DOJ Study

The Supplemental Study to the DOJ Report

The 2006 RAND Study

Related Links

-

roles)) {

// user is not associated with role, redirect to signup page

?>

- Definitions of Key Terms

- The Expansion of the Federal Death Penalty

- Roster of Current Federal Death Row Prisoners

- Please register or login for free access to our collection of supplementary materials.

With the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, the federal death penalty returned 16 years after Furman v. Georgia overturned existing capital punishment statutes. Since that time, there has been evidence of racial and geographic disparities in the federal death penalty. A study in 2000 by the Department of Justice found that such disparities existed; however, other studies have maintained that the disparities were not due to bias. The debate continues over whether certain racial groups and individuals from certain locations in the United States are more likely to be authorized by the Attorney General for the federal death penalty.

Issues Highlighted by the Juan Garza Case

During Garza’s appeals, his attorneys referred to the Department of Justice’s Report on the Federal Death Penalty System: A Statistical Survey (1988-2000). When the report was released in September 2000, President Clinton postponed Garza’s second scheduled execution date to June of 2001 so that the Department of Justice (DOJ) could further study possible bias in the federal death penalty.

-

roles)) {

// user is not associated with role, redirect to signup page

?>

- Juan Garza Timeline

- "A Report on the Federal Death Penalty System: A Statistical Survey (1988-2000)" from the DOJ

- Amnesty International Memorandum to President Clinton (139 KB)

- Citizens for a Moratorium on Federal Executions

- Please register or login for free access to our collection of supplementary materials.

The DOJ report showed that from 1988 to 2000, 30% of all federal capital cases originated in Texas. Of the Texas cases submitted to the Attorney General’s office, the federal death penalty was authorized in over 50%. Furthermore, Hispanics were 2.3 times more likely than non-Hispanics to be authorized by the Attorney General for federal capital prosecution. Garza, a Hispanic man from Texas, was tried during time period covered by the study, and Garza’s attorneys claimed that the federal death penalty system was biased against offenders with Garza’s racial and geographic characteristics, making him more likely to receive a death sentence than a white person or someone from another state who was accused of the same crime.

The findings of the DOJ report and the characteristics of Juan Garza’s case, stimulated public efforts calling for a moratorium on federal executions. One group, the Citizens for a Moratorium on Federal Executions, stated that no executions should take place until it could be conclusively verified that there was no racial or geographic bias in the federal death penalty.

Findings of the DOJ Study

The Justice Department’s Report on the Federal Death Penalty System: A Statistical Survey (1988-2000), commissioned by President Clinton, presented statistical information on the racial, ethnic and geographical distribution of defendants and their victims at different stages of the decision-making process (arrest, conviction, sentencing, execution). The study did not control for other variables such as the severity of the crime or the record of the defendant.

In researching the federal death penalty, the DOJ split its data into two periods, "pre-protocol" (1988-1994) and "post-protocol" (1995-2000), because the procedures changed after the passage of the Federal Death Penalty Act of 1994. (See The Expansion of the Federal Death Penalty).

Before the Federal Death Penalty Act of 1994, U.S. Attorneys did not have to notify the Attorney General unless they wished to seek the death penalty against a defendant, thus there is no data on all capital-eligible crimes. In this period of the study (from 1988 to the end of 1994), U.S. Attorneys sought approval from the Attorney General to seek the death penalty in 52 cases and received approval in 47 cases.

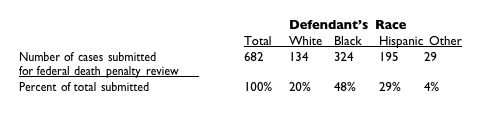

In 1995, the Department of Justice adopted a protocol that required U.S. Attorneys to notify the Attorney General of all cases in which a defendant is charged with a capital-eligible offense, regardless of whether the U.S. Attorney wanted to seek the death penalty in that case. The cases are considered by a Review Committee of senior Justice Department attorneys that makes a recommendation to the Attorney General. From January 27, 1995, to July 20, 2000, U.S. Attorneys submitted 682 cases for review and the Attorney General ultimately authorized seeking the death penalty in 159 of these cases. Thus, the post-protocol data provides a fuller picture of the decision making process because all possible capital cases are considered.

Race

The DOJ study found numerous racial disparities, including the fact that 80% of the cases submitted by federal prosecutors for death penalty review from 1995 to 2000 involved racial minorities as defendants (See table).

Even after review by the Attorney General, 72% of the cases approved for death penalty prosecution involved minority defendants.

Likewise, of the 677 homicide cases submitted for review from 1995 to 2000, 500 (74%) of the defendants were charged with intraracial homicides (i.e., the defendant and the victim were of the same race/ethnicity) and 177 (26%) were charged with interracial homicides (i.e., the defendant was of a different race/ethnicity than at least one victim). U.S. Attorneys were almost twice as likely to recommend the death penalty for a black defendant when the victim was non-black (36%) as when the victim was black (20%). In comparison, U.S. Attorneys were about equally likely to recommend the death penalty for a white defendant when the victim was non-white (35%) rather than white (38%).

The report found that from 1995 to 2000, a white defendant was almost twice as likely as a black, Hispanic, or "other" defendant to be offered a plea agreement reducing the penalty to life imprisonment or less. Forty-eight percent of white defendants entered into plea agreements as opposed to about 25% of black, Hispanic, or "other" defendants.

Geographic Disparities in Seeking the Death Penalty

The survey also reported large disparities in the geographical distribution of federal death penalty recommendations. From 1995-2000, 42% (287 out of 682) of the federal cases submitted to the Attorney General for review came from just 5 of the 94 federal districts. The five districts were the District of Columbia, Maryland, New York (Eastern), New York (Southern), and Virginia (Eastern). The four districts of Texas in total submitted 28 defendants for review by the Attorney General (4% of the 682 total).

After the release of the DOJ report, Attorney General Janet Reno said she was "sorely troubled" by the results of the report and recommended further investigation in order to determine the cause of these disparities.

The Supplemental Study to the DOJ Report

-

roles)) {

// user is not associated with role, redirect to signup page

?>

- "Federal Death Penalty System: Supplemental Data, Analysis and Revised Protocols for Capital Case Review" from the DOJ

- The Testimony of a Former Federal Prosecutor Before the Senate on Race and the Federal Death Penalty (89KB PDF)

- Professor Baldus’ Comments on the Supplementary Study

- McCleskey v. Kemp 481 U.S. 279 (1987)

- Please register or login for free access to our collection of supplementary materials.

In June 2001, under a new administration, the DOJ released Federal Death Penalty System: Supplemental Data, Analysis and Revised Protocols for Capital Case Review, the supplemental study to The Federal Death Penalty System: A Statistical Survey (1988-2000). The supplemental report included information from U.S. Attorneys on potential capital cases that were not submitted to the Department of Justice for review and also examined the factors taken into account when deciding to pursue a case in the federal system. (The first DOJ report on the federal death penalty only examined cases submitted to the Attorney General). The report outlined possible future research on the federal death penalty system.

The information collected from the U.S. Attorneys on potential federal capital cases in which the death penalty was not pursued yielded findings similar to those in the original report on the federal death penalty. Of the 973 cases reviewed, 17% (166) involved white defendants, 42% (408) black defendants, and 36% (350) Hispanic defendants, all percentages that differ sharply from the percentages of these groups within the general population of the United States.

The supplemental study found that there was no evidence of favoritism toward white defendants. Of the submitted cases, capital charges were sought for 81% of the white defendants, 79% of black defendants, and 56% of Hispanic defendants.

Professor David Baldus’ Comments on the Supplemental Study

Law professor David Baldus, whose work on race and the death penalty brought about the 1987 Supreme Court case McCleskey v. Kemp (See Race and the Criminal Justice System), criticized the results of the supplemental DOJ study.

Remaining unconvinced that “there is no significant risk of racial unfairness and geographic arbitrariness in the administration of the federal death penalty,” as the supplemental study proclaimed, Professor Baldus noted that the supplementary report ignored the evidence of race-of-victim discrimination that appeared in the original report. The supplemental report, according to Baldus, also did not clearly address the geographic disparities in the federal death penalty (See “Professor Baldus’ Comments on the Supplementary Study”). Baldus noted that whites were more likely than blacks to be granted plea agreements to non-capital charges, thus eliminating the threat of the death penalty.

The report also misrepresented “the nature of race discrimination in the administration of the federal death penalty,” according to Baldus. Baldus did not disagree with the findings of both the original DOJ report and the Supplemental Study that whites have a higher rate of federal death penalty authorization than blacks. However, he maintained that the DOJ misinterpreted these results. Regardless of the race of the defendant, prosecutors are more likely to seek the death penalty for those who murder whites. In the majority of murders, the killer and the victim are of the same race. Thus, whites are not in fact treated more harshly by the federal death penalty system; instead, it is because whites are more likely to murder other whites than any other race that more whites are authorized for the federal death penalty. This implied that the black lives were considered less valuable because the death penalty is not sought as often when they are victims.

Baldus called upon the government to study this issue further.

The 2006 RAND Study

-

roles)) {

// user is not associated with role, redirect to signup page

?>

- The RAND Study

- Prof. Zimring's Evaluation of the RAND Study (28 KB)

- The ACLU's Report on Racial Disparities in the Federal Death Penalty

- Department of Justice Responses to Inquiries from Sen. Russell Feingold, in Preparation for Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution Hearing On “Oversight of the Federal Death Penalty” (June 2007) (706KB PDF)

- Please register or login for free access to our collection of supplementary materials.

A 2006 study of federal death penalty cases from 1995 to 2000 by the RAND Corporation found no evidence of racial bias. The RAND study examined the files of 652 defendants who were charged with capital offenses between January 1, 1995, and July 31, 2000. Even though the investigators found that the death penalty was more often sought against defendants who murdered white victims, researchers ultimately concluded that the characteristics of the crime, and not the racial characteristics of the victim or the defendant, could be used to explain whether federal prosecutors would seek the death penalty.

The RAND report noted that U.S. attorney offices in the South forwarded the majority of the 652 cases sent for review, and this region accounted for about half of the recommendations to seek the death penalty. After reviewing the cases, the Attorney General decided to seek the death penalty for 25% of the 600 defendants considered. In addition, approximately 50 defendants reached plea agreements after their cases were submitted by U.S. attorneys, but before the attorney general made a decision about whether to seek the death penalty. Most of the homicide cases that were studied involved victims of the same race as the defendants. For example, white defendants were more likely to kill white victims than African Americans or Hispanics.

The authors of the study noted the limitations of the study. They wrote in the Executive Summary of the Report that:

[T]he three teams agreed that their analytic methods cannot provide definitive answers about race effects in death-penalty cases. Analyses of observational data can support a thesis and may be useful for that purpose, but such analyses can seldom prove or disprove causation….

In summary, given the inherent problems in using statistical models under these circumstances, our results need to be interpreted cautiously. There are many reasonable ways to adjust for case characteristics, but no definitive way to choose one approach over another. Bias could occur at points in the process other than the ones studied, such as the decision by federal prosecutors to take a case. Results could be different with other variables, methods, and cases. Extrapolating beyond the data we analyzed here to other years, other defendants, other points in the decision-making process, or other jurisdictions would be even more problematic.

Shortly after the study was released, six well-known researchers hired by RAND to be “expert consultants” voiced their concerns about the study. One of the six researchers, Professor Franklin E. Zimring, was concerned that the RAND Corporation drew conclusions from a very limited set of data and only used data from a part of the federal death penalty process, not the whole. By using cases selected from the “mid-point” of the process, Zimring argues, how a case comes to be selected for the federal death penalty as well as what happens after it is selected (i.e., possible plea agreements) is left out. To ascertain whether there is truly bias in the federal death penalty system, the whole process needs to be studied.

Questions for Further Analysis:

-

Revisit the Juan Garza narrative. Did the government handle Garza’s case fairly after the release of the first Department of Justice study on the federal death penalty? Why or why not? Does your answer change after reading the results of the Supplementary study?

-

Was the Bush administration’s decision to go forth with Garza’s execution later vindicated by the RAND study? Why or why not?

-

Read one or more of the studies on the federal death penalty and critique its methodology. What would you alter and what limitations would arise from those changes?

Related Links

The Expansion of the Federal Death Penalty

Race and the Death Penalty

The Case of Juan Garza